The Stamford Historical Society Presents

Pride and Patriotism: Stamford’s Role in World War II

Online Edition

The Interviews

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The book may be viewed at the Marcus Reseach Library of the Stamford Historical Society.

With permission by the author.

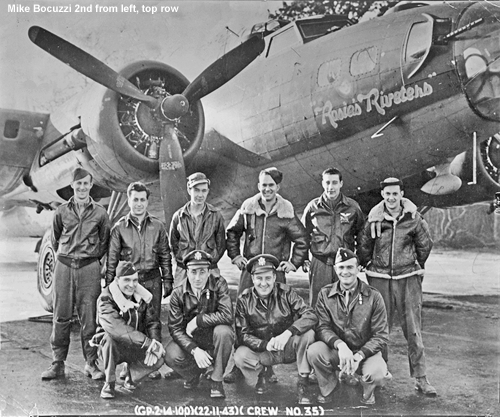

Mike Bocuzzi

Mike was one of four brothers to serve in World War II. Assigned to the Army Air Corps, he was a radio operator and gunner for “Rosie’s Riveters,” a B-17 so named for its pilot, Robert Rosenthal. As part of the Eighth Air Force, Mike flew 25 bombing missions over Germany from October 1943 to March 1944. This was one of the most dangerous times in the war, and at one point, one out of three crewmen did not return from a bombing mission. The B-17, or “Flying Fortress” as it was called, had a ten-member crew, and Mike worked every position except as ball turret gunner.

I was 20 when I went in. I got the nickname “Foxhole” because of my height (5’ 3"). One time during the roll call, the Drill Sergeant yells to me, “Hey, Bocuzzi, get out of the foxhole.”

I was 20 when I went in. I got the nickname “Foxhole” because of my height (5’ 3"). One time during the roll call, the Drill Sergeant yells to me, “Hey, Bocuzzi, get out of the foxhole.”

“Rosie’s Riveters” had great ethnic balance. We had an Italian, a Jew, a German, an Irishman, and a Scotsman. (An article in YANK, a military magazine, once referred to them as a “mongrel crew.”)

My first actual bombing missions were October of 1943, the 12th, 13th and 14th I think. We hit Munster, Bremen, and Schweinfurt. Munster and Bremen were marshalling yards.

Schweinfurt was a ball bearing plant. We flew out of Thorpe-Abbotts, England. At that time we didn’t have flying escorts. Once you got over the (English) Channel, you were all alone. The only time it was quiet was when you were climbing and forming into a group, and even at that time, you had equipment to check and a lot of heavy flying equipment. We had to wear an electric flying suit because it could get to 60 degrees below zero in the B-17. You had a heated suit that plugged into the airplane. We had no helmets or anything. Parachutes? We didn’t know what they were. We’d move them out of the way; push them around the plane. With all the stuff we had on, we couldn’t be bothered with a chute.

We went through four different airplanes while I was there. In fact, one time when we came back from a raid on Bremen, our number two engine was shot out, the number four engine was out, and we had a hole eight feet in diameter in our right wing. Later we counted 176 holes in the plane.

There were times that we were coming in and we had to dump all the excess weight off the plane – chutes, bullets, the magazines, everything. One time I even threw my pilot’s hat off – imagine that!

On one mission, we came back alone. It was October, 1943, a bombing mission over Munster. One by one the planes went down until it was just us. Our two waist gunners were wounded. (One later died.) This was right at the beginning of the war for me. We were broken in right. After the mission, we were all drained. To be honest, when we landed, I couldn’t move. I just couldn’t move a muscle. But the other guys left me alone. They didn’t make a big deal of it. After this, they sent us on R & R. (This episode is written up in YANK April, 28, 1944.)

I shot down my first plane that same month – a 190. In fact, I swear to this day that I saw a kid’s face as the plane was going down. He was so young. As he came toward us in a swoop, I hit him, and he came in so close that he took the antenna right off our ship. I can visualize that today like it was yesterday.

You always had to stay in formation, no matter what. Once you dropped formation, you were dead. The B-17 could take a lot of punishment. You’d see planes come in with a tail torn up, an engine out, a fuselage ripped open. Sometimes the flak was so close that you could smell it. Of our ten crew members, four were wounded and two didn’t come back. I was never wounded. I guess I ran faster than the bullets.

The Hamburg mission was horrendous. The British bombed them by night, and we bombed them by day. What we did there was unbelievable. Fires everywhere – everything destroyed. But you couldn’t think about that. You had a job to do. (Accounts of the Hamburg bombings bear this out. The fires were so severe that fire storms were created by the temperature.)

Yes, one time I did help the pilot land, but it was no big deal. The co-pilot, “Pappy” Lewis, was wounded. We pulled him out of the seat, and I had to jump in. I only assisted the pilot. The plane was damaged, but we made it back all right.

We also flew one of the longest raids in the war – all the way to Trondheim, Norway (1900 miles). We didn’t know too much about this mission except that we had to bomb some plants. I think they may have had something to do with the atomic bomb. (Accounts of this raid mention only that German naval installations were bombed.)

We needed every drop of fuel to make it back. The average mission was about 6 hours; Trondheim was 12 hours.

My last mission was March 3. 1944. We were among the first Americans to hit Berlin. But the difference between this and our earlier raids was like night and day. Now we had escorts – Spitfires, P-5 Mustangs, the works. It was like going for a joy ride compared with our first missions.

None of us ever felt like heroes. We just felt like it was something we had to do, not by choice, of course. I always complained and moaned that I wasn’t going up anymore, but when they called the next raid, we were always there. They say we were heroes. But we did what we had to do. One time Shaeffer (the waist Gunner) got hit and had a hole in his chest. I unplugged my oxygen and went to help him. I found some rags and packed them into his chest. Then I gave him the portable oxygen tank. I didn’t make it back to my oxygen and passed out. Then Bill DiBlasio (waist gunner) plugged me in and saved my life.

I was in trouble a lot of times. I was busted to Private a few times. One time two MPs came to get me. They were so much taller than me that everyone would say, “Look at that poor little guy.” One time, instead of busting me, they gave me K.P. Imagine – I was a Tech Sergeant and I was on K.P.!

All in all, though, I don’t think I would trade my experiences with anyone. Sure it was dangerous, but we did our job, and I made a lot of lifelong friends.

Mike won two Distinguished Flying Crosses and five Air Medals, one of which was presented by Jimmy Doolittle. Many of the exploits of

“Rosie’s Riveters” were written up in “Yank,” “The Bridgeport Herald,” and “The Advocate”.

© Anthony Pavia, 1995

Mike Bocuzzi second from left, top row

United States Army Air Forces / Eighth Air Force

Overview of Air Force Combat Units of World War II

The Movement Toward Air Autonomy

Introduction

Introduction

Veterans

Battles

Stamford Service Rolls

Homefront

Exhibit Photos

Opening Day