The Stamford Historical Society Presents

Pride and Patriotism: Stamford’s Role in World War II

Online Version

The Interviews

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The interview below is from AN AMERICAN TOWN GOES TO WAR by Tony Pavia, 1995, ISBN: 1563112760

The book may be viewed at the Marcus Reseach Library of the Stamford Historical Society.

With permission by the author.

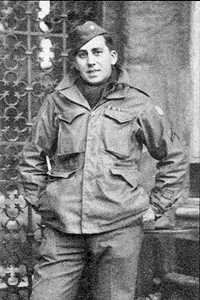

Leon Dzilinski

Leon Dzilinski was working at Pitney Bowes when he entered the army in 1943. He was trained as a medic and assigned to the 5th Army headed by General Mark Clark. After being stationed in North Africa he participated in the invasions of Sicily and Italy.

At first I wanted to join the Marines so I went into New York with my buddy Matt Guzda to sign up. He got in but they wouldn’t take me because I was colorblind. I guess I was the lucky one. He was killed at Guadalcanal.

At first I wanted to join the Marines so I went into New York with my buddy Matt Guzda to sign up. He got in but they wouldn’t take me because I was colorblind. I guess I was the lucky one. He was killed at Guadalcanal.

I was trained as a medic. We were aidmen, litter bearers (stretcher carriers), ambulance drivers, whatever. Each infantry company had 125 men. They had one aidman and one medic.

While they were in combat they couldn’t take care of all those men so that’s when they called us. We were the reinforcements to help them clean up the wounded. We gave them morphine and carried them back to the aid station. From there they’d get to a hospital.

We didn’t carry any weapons. We were non-combatants. But the only way to tell was by the cross that we had on our arms.

I landed in Oran (North Africa) in 1943. We stayed there until we made the invasion of Sicily. We landed at Gela and from there we went to Palermo, Messina, and later to Italy.

In Sicily I was attached to the 54th Medical Battalion. I think the whole campaign only took 43 days. We went right in with the infantry at Gela. We had to evacuate the wounded on foot because there were no jeeps on the front line. It was bad there and we had to administer a lot of morphine. Then we’d have to tag the guys so that the doctors wouldn’t repeat the dosage. You did whatever you could. You’d take the first guy you came across, pick him up, and get out of there. After a while you got used to it and it became a routine job. (In Sicily alone the 54th Medical Battalion won 2 Silver Stars, 55 Bronze Stars, and 26 Purple Hearts.)

It was dark before daybreak when we hit the beaches in Sicily. It was so bad because there was so much confusion there. Our paratroopers were supposed to be dropped in 10 miles behind the German lines and fight back toward the beach. But before this happened some German bombers came over and attacked us. So when our planes with the paratroopers came over later, our own ships fired on them because they thought it was the Germans again. I saw Stan Kaslikowski there. He was wounded but he had already been cleaned and taped up. I had a pair of rosary beads and gave them to him.

When we invaded Italy we went over the Straits of Messina to Napoli. This time it wasn’t bad. The Germans had already taken off and we just walked right in. Probably the scariest time I had was when we had to walk right over Mount Etna. It was an old volcano and all I kept saying was, “Don’t blow up now! Don’t blow up now!”

We went through town after town-Santa Maria, Casserta. We moved so fast I can’t remember all of them. At Cassino the Germans had a vantage point that overlooked the entire Po Valley. The British 8th Army finally took it but they were using Polish troops…and over 5,000 of them were slaughtered. We went in later to clean up.

After the Po campaign we went into Rome. This time we were attached to the Special Services because they needed medics. They were good soldiers and nobody wore stripes so you didn’t know who the officers were. Once I asked a guy who was in charge and he said, “We’re all equal here.”

After we took Rome a few of us were awarded the Bronze Star. I don’t know why. All I know is that one day in Traversa our commander called us in and told us to put on our dress uniforms. Then General (Geoffrey) Keyes awarded them to us right in the field. (The Bronze Star was awarded to Dzilinski and two other medics. The citation reads as, follows… “For heroic action in combat on June 4, 1944 in the vicinity of Rome, Italy…These enlisted men advanced under enemy ire and our own troops crossfire across 200 yards of open field in front of our advancing tanks and successfully evacuated three machine gun casualties.”) We were attached to a lot of units in Italy, the Third Army, the Ninth Division, the 85th, 88th, the 96th. I was even with the 34th Division for a while. That’s the one Senator Inoye was with when he lost his arm. They were the Japanese-American unit, the 442nd Regiment, 100th Battalion. They were called Nisei. They treated me the best out of any other outfit I was in. One guy always used to say, ”Leon, we’re not Japanese, we are American.” One of the guys was from Stamford. His family owned a restaurant above Frank Martin and Sons. When the war was over I looked him up and they gave me a huge meal, for nothing. They were great fighters and showed that they were just as American as anyone else.

For a while I was even attached to Senator Dole’s 10th Mountain Division. They even trained us on how to bring the wounded down the mountain by rope. We never did it that way because it was quicker just to slide the stretcher down the slope.

We saw a lot of young soldiers get killed. When the infantry was losing a lot of men they brought in a lot of replacements. These young kids were called “Repo-Depos.” They were green and sometimes didn’t even get down when a shell came in. You’d have to yell at them to get down. Compared to them I was a seasoned old vet.

We slept outside a lot of the time. When it was cold you’d do anything to get warm. I even remember once we were near a cemetery and we slept in the mausoleums just to stay warm. I was lucky though. I never got hit. I don’t know why. I remember one night we were getting shelled and an infantry man ran up to me and said, ”I’m not getting in that hole with you. You don’t even have a gun.” I thought, “What the hell good is a gun going to do?” So he dove into another hole and was killed. He would’ve been better off with me.

All of the infantry guys were wonderful men. They’d have head wounds or stomach wounds but they never complained. They were so happy to see us. Sometimes at night it would be so dark you couldn’t see a thing in front of you but you would hear moaning all around. I’d get my men together and we’d go out there and find them. Somebody had to get them. You couldn’t just leave them there. Sometimes you’d pick up a guy who was over 200 pounds but you had to do it. They never complained. So you’d lug a guy in and you’d be exhausted and the Sergeant would order you back out. My nickname was Diesel and I remember he’d say to me, “Diesel you just have to get those men out of there.”

Sometimes we’d follow the infantry right into a town. If somebody got wounded, we’d have to run right out into the street to get them. It wasn’t good for other men to see their buddies lying there wounded so we had to get them to the rear as quickly as possible.

One time my brother looked me up and found me in a small town in Italy. He was with the 8th Air Force and he was used to good treatment. The first night he said to me, “Where do we sleep?” And I said, “Right here on the ground. Where do you think?” The next morning we went to the evacuation hospital for breakfast and he said, “Leon, you guys live like bums.”

Toward the end of the war I ended up in Cortina, a resort town. We were like prison guards watching over the Nazis. I met a few of the Polish P.O.W.s and they told us that they were forced to fight with the Germans. Later, a few of the guys refused to go back to Poland and went to live in Canada and England.

The Italians were glad to see the Americans. A lot of them couldn’t wait to get rid of the Germans. They treated us wonderfully and gave us wine and cheese. We had no trouble with them and were greeted with open arms.

After a while the Germans began to surrender by the thousands. They knew that the war was lost and some simply walked into town and gave up. Once, when I was in a bar in Cortina, a bunch of Germans just walked in and tried to get a drink. Then they surrendered.

When the war in Europe ended we were supposed to go to Japan, but then we dropped the bomb and that was it.

I never met General Clark during the war but a few years ago he came to the Memorial Day Parade in Stamford. I went up to him, shook his hand, and showed him my 5th Army Patch. I said, “Sir, you were a great General.” And he smiled, put his arm around me and said, “I’m always so happy to see men who were under my command.”

Leon returned to Stamford and to his job at Pitney Bowes. He worked therefor over 40 years until his retirement. In addition to his Bronze Star he was awarded a “V” for valor and second Oak Leaf for evacuating patients under fire on the Gothic Line.

© Anthony Pavia, 1995

Introduction

Introduction

Veterans

Battles

Stamford Service Rolls

Homefront

Exhibit Photos

Opening Day